Since 2010, I have been creating ceramic portrait busts that explore the abstract edges of figurative representation. They vary stylistically and in terms of color palette, surface and scale. They range in height from five inches to between two and three feet tall.

My most recent exhibition, rough edges, at Studio10 in Brooklyn, NY was comprised of twelve busts mounted on raw plywood stands that positioned each bust at eye level. They filled the entire space of the gallery and were configured randomly, approximately 3 feet apart. All the busts faced the door so that upon entering, you confronted the full gaze of the entire group. The sculptures were looking at you looking at them. The spacing made it possible to then walk into the installation as well, to experience and connect with each sculpture as an individual.

Although each of my sculptures is a distinct individual, none are portraits of specific people. Rather they are meant to embody familiar psychic states while remaining open-ended, allowing viewers to bring a wide range of projections to the encounter. The challenge for me is to imbue each piece with the immediacy of human experience, and through the process of making, allow each sculpture to project a sense of its hidden life—to create an object that comes to life while remaining a thing.

My artwork has taken various forms over the course of my career but my underlying motivation has been constant – the desire to give concrete form to fragmentary bits of consciousness: moments of inner conflict, disquiet, ambivalence and unease; and in doing this, create work that generates a psychological tension with the viewer.

My visual inspiration comes from a wide range of sources. I’m most drawn to figurative sculptures and sculptural objects that appear to have had some other cultural function, either in ritual or in daily life, in addition to being creative expressions. These are objects that humans have empowered: idols, reliquaries, masks and even toys.

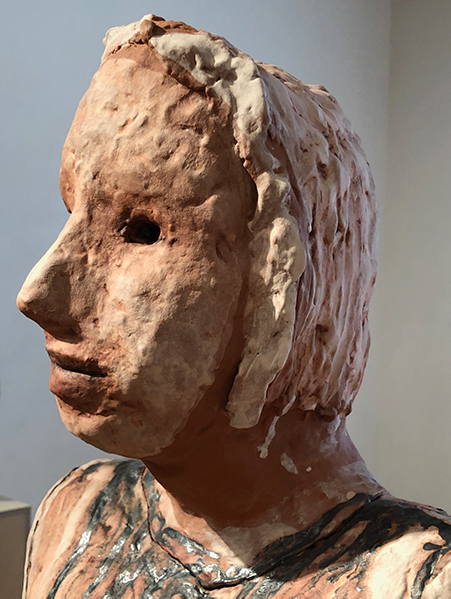

I’ve taken formal cues from the abstracted features and exaggerated forms of the Jomon Dogu figures of Neolithic Japan, as well as the hollow eyes of the Haniwah funeral figures from the third to sixth century A.D. For me, these sculptural objects—everything from Renaissance reliquary busts to medieval European iron helmets and African masks – continue to resonate as their meanings evolve over time.

My process is primarily intuitive and spontaneous. I have strategies, but try to keep them below the level of conscious awareness. For instance, I often contrast facial features that are quite abstract, stylized or distorted, with subtle facial expressions and body language that are more convincingly accurate. I think the tension between the two can create a surprising uncanny sensation.

I sometimes use color to heighten mood and expression, and sometimes to interfere with expectations. I like to use traditional glazes, such as the thick shiny white of Majolica or the cobalt blue of Delftware. However, I employ them in non-traditional ways by smearing them and allowing them to drip and run. For me, shiny glazes suggest other ceramic objects such as vessels, and a feeling of containment. Dry, matte surfaces evoke the kind of rawness and vulnerability that I find is more conducive to personal projection. I often use both in the same piece.

The meaning of what I do is very much embedded in process—in all the ways I connect to my material. As much as possible, I want everything I perceive and feel and do in this process to be revealed in the resulting object.

From early childhood and for most of my art career I have made things out of clay. No other material rivals clay’s immediacy, its capacity to register and record touch, and its ability to capture the experience of making.

I think of what I do as a kind of intimate interaction with the clay: a conversation, a dance, an exploration, or a wrestling match. Mainly, it’s an engagement in the unpredictable present moment, rather than an attempt at control. Hopefully, the resulting sculptures are embodiments of this experience.

Because the portrait bust is such a familiar sculptural object, it is loaded with associations and expectations. I think that when some of these are subverted, things can shift and feel a little less certain, allowing a moment of encounter to open up, where the unexpected can occur.